Публикации

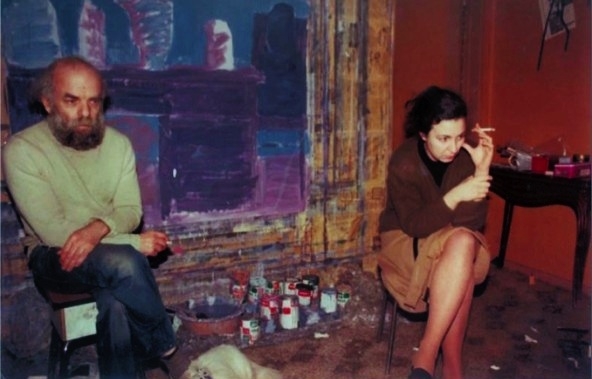

Head-to-head in Europe, but face-to-face in America: Tselkov’s ‘Golgotha’ next to Roginsky’s ‘Red Door’ in the Zimmerli Museum, New Brunswick, courtesy of Simon Hewitt

Two of Russia’s greatest Non-Conformist artists go head-to-head across Europe this Summer: Mikhail Roginsky in Venice and Oleg Tselkov in Moscow.

Both were born in the Russian capital in the early 1930s, grew up during World War II, studied art at theatre school, and were exiled to Paris in the late 1970s – pursuing isolated careers unaffiliated to any movement. But the similarities stop there. Stylistically they are poles apart. Roginsky used a dull palette so matt it feels he rubbed sandpaper over the surface. Tselkov’s shiny paintwork gleams like enamel. Roginsky hardly ever painted faces. Tselkov hardly ever painted anything else.

*

Beyond the Red Door, featuring 120 works produced by Mikhail Roginsky (1931-2004) after he emigrated to France in 1978, is one of the major Collateral Events at this year’s Venice Architecture Biennale, and his first solo exhibition since 2006. The venue is the 15th century Palazzo Giustiniani by the Grand Canal (where Wagner wrote part of Tristan und Isolde in 1858/9) and the show runs until September 28.

The presentation, designed by Moscow artist/architect Evgeny Asse, makes imaginative use of dull-coloured backcloths (grey, brown, olive-green) and diagonal walls. Asse says he strove ‘to demonstrate independence from the context.’ He had little choice: the medieval palazzo would be considered totally unsuitable for contemporary art anywhere else but Venice. Asse makes a virtue of the venue’s small volumes, but the upstairs lay-out is labyrinthine and disorienting and, with their low-ceilings and cut-cornered walls, these spaces feel almost claustrophobic. That may be the aim, but I am not sure Roginsky benefits from being forever imprisoned in settings designed to recall a kommunalka (Soviet communal apartment). The Russian Non-Conformist exhibition at the Saatchi 18 months ago, where Roginsky’s works were hung on walls painted a lurid green, was guilty of the same clichéd approach.

The Venice exhibition greets visitors with Roginsky’s famous Red Door, the only work that hails from his Moscow years. Its presence is misleading, implicitly associating Moscow-based Roginsky with Conceptualism – as if in contrast to the Paris paintings which make up the rest of the show. His commitment to painting was constant throughout his career.

Works are hung over two floors in eight rooms, each with a different theme. The first is dominated by still lifes of shelves – most lined with bottles, some stacked with papers; one dissolves into grey/black horizontal abstraction.

Other works – seven of them owned by the veteran Russian photographer Vladimir Sichov (now based in Berlin), who hosted Non-Conformist exhibitions in his Moscow flat back in the 1970s – offer a surprisingly bright contrast. Roginsky’s ability to conjure up a plastic bottle from a few rough strokes of blue amounts to genius.

The second room features the still lifes of objects from mundane Soviet reality – kettles, stoves, bottles, gas-rings – with which Roginsky is most readily associated. But to find these works dating from 1991-2003 is disconcerting: Roginsky first painted them in the mid-60s. The exhibition’s absence of earlier works prevents pre/post-exile stylistic comparison and exposes the Parisian Roginsky, perhaps unjustly, to charges of repetition and self-pastiche.

The third room is devoted to garments painted in phthalic glycerol in 1991/92. Shirts, jackets and trousers occupy the surface – corrugated cardboard, not canvas – in an explosion of drab, disorientating ugliness that propels Minimalist banality into the artistic stratosphere. This is tough, unblinking art, and these are works of high daring (and, one fears, physical fragility). They assert Roginsky as one of the bravest and most technically accomplished painters of his era.

The other stand-out room – the largest in the exhibition – is upstairs. It features several epic works (up to 8ft high) in acrylic on paper from Roginsky’s 1981 Pink Interior series, which does for The Paris Flat what his earlier still lifes did for The Communist Kitchen. Ladders, chairs, tables, radiators and wiring blend their mournful poetry with a compositional discipline that veers towards abstraction. Several other works exist in this series: their absence from the Venice show is almost criminal. The full ensemble would grace any museum, and constitutes Roginsky’s towering achievement.

The rest of the show cannot scale such heights, but there is humour. Roginsky’s occasional recourse to meaningless phraseology involves ungainly script that pokes fun at Bulatovian graphic precision and Kabakovian conceptualist verbosity. When using French, Roginsky adopts a Russian И instead of a Western U – much as Western book titles or movie posters idiotically adopt Я for R if their subject is Russian. Some Roginsky works have so much verbiage they resemble pages of Pravda.

The humour is laced with nostalgia, and it is surely significant that many of Roginsky’s last works took Moscow as their theme: its streets, interiors, courtyards, Metro, slush, façades…. The mood of shabby listlessness perfectly conveys – one imagines – the colourless tedium of Soviet everyday life. They look like eye-witness accounts, and doubtless were, but it is disquieting to find that they were painted not in the 1960s and ’70s but between 1995-2001.

Yet there are shafts of sunlight at the end of the Socialist tunnel. A 1998 view of Krasnolselskaya metro station adds a pinky-yellow glow to the walls, and imaginary red lustre to the top of the columns. At An Exhibition (also 1998) features 16 figures with their backs turned to picture-lined walls; all are clad in long dark coats… except for a young woman in an anarchic mini-skirt, red jacket and yellow scarf. Metro Entrance from 1999 – arguably Roginsky’s final masterpiece – contrasts the station’s bleak, grey-blue concrete exterior with a shimmering ticket hall glimpsed through glass doors, transformed by tantalizing streaks of green, red and yellow into an unlikely fairy-tale palace.

The exhibition is accompanied by a 176-page catalogue featuring essays by Russian art critic Evgeny Barabanov, exhibition curator Elena Rudenko, French art critic Richard Leydier and Silvia Burini (head of the Italy-based Centro Studi sulle Arti della Russia). All mention Roginsky’s reputation as the father of Soviet Pop Art – three to refute it, Leydier to claim Roginsky was influenced by Robert Indiana and should be compared to Jim Dine.

I don’t see the mass-consumerism of Pop Art in Roginsky’s utilitarian utensils; their subject-matter and the materials he uses (cardboard often preferred to canvas) have more in common with Arte Povera. But I agree with Leydier that Roginsky’s domestic interiors have the weighty silence of Hopper (whose influence Leydier traces to the American National Exhibition held in Sokolniky Park in 1959). The technique he uses to create reflections makes me think of Hockney, and his vehement grey backgrounds of Giacometti.

Other purported influences on Roginsky, cited in these essays, are more historic – dating from Dubuffet, Duchamp and Monet back to Goya, Brueghel and Piero della Francesca. Personally, I find Roginsky’s dappled paintwork and flattened perspectives evocative of Bonnard and Vuillard, and his abstemious still lifes of Bonvin and Chardin.

Silvia Burini links Roginsky to Rabin and Rukhin; earlier Russian influences surely include Tatlin and Larionov, while his ironically titled 1988 oil-on-plywood On a Confiance aux Institutions Etatiques, with its orange table-top viewed from above, placed diagonally on a green ground, seems to reinterpret the Russian Avant-Garde.

The Venice exhibition is staged by the Mikhail Roginsky Foundation, founded by the artist’s widow Liana earlier this year with a raft of ambitious goals that includes compiling a catalogue raisonné and allocating grants for studies devoted to Roginsky or other Russian émigré artists. Liana is keen for Roginsky to be considered a Franco-Russian – rather than a purely Russian – artist, so as to boost his reputation in the West, where he has been treated with relative indifference (especially from a commercial point of view). But that aim is not enhanced by having the Foundation based in Switzerland (Lugano), and presided over by Moscow-based Inna Bazhenova, owner of The Art Newspaper Russia (and of eleven works in the exhibition).

Let’s hope the Venice show will herald an upsurge of interest in Mikhail Roginsky’s understated yet powerful art, and that his reputation will one day approach that of two other Russian-born artists who found fame outside their native land: Marcus Rotkovich and Nikolai Shtal von Golshtein… better known as Mark Rothko and Nicolas de Staël.

*

TSELKOV TURNS EIGHTY IN MOSCOW

Бубовный Туз (Ace of Diamonds), the Moscow show devoted to Oleg Tselkov, is staged at the Ekaterina Foundation near Lubyanka. It opened on June 4 and runs until August 10, with 44 works spanning Tselkov’s career from 1963 to 2010. The majority are owned by Tselkov himself; ten by Foundation owners Vladimir & Ekaterina Seminikhin; and five by the legendary Russian poet Evgeny Yevtushenko, a friend of Tselkov’s since they were North Moscow neighbours in the 1960s.

The exhibition marks Tselkov’s 80th birthday and his presence at the vernissage – on possibly his last trip to his motherland – attracted extensive media coverage, including a 40-minute documentary on culture channel Rossiya K.

Although the exhibition has almost three times fewer works than the Roginsky show, it feels much bigger due to the Ekaterina Foundation’s spacious white-walled galleries, extending over two floors; and to the sheer size of many of the paintings (up to 9 x 13ft) – often hung one to a wall.

The exhibition begins with four works from the 1960s, when Tselkov employed a vibrant, neo-Fauve palette that could not be further removed from the subdued tones favoured by Roginsky or most of his other Soviet contemporaries. A fleeting passion for strident flowers worthy of Georgia O’Keeffe is evident in a 1964 Portrait of a Woman, who looks as if she is being attacked by triffids. Another Portrait of a Woman features a red-faced figure with hair like strands of liquorice, half-emerging from behind a stage-curtain, her giant hand pointing at the viewer like Trotsky’s Red Army recruitment poster.

Tselkov’s works of the early 1970s saw a radical change in style as he adopted a dark red palette overshadowed by Rembrandtian murk, and temporarily explored portraiture. Rembrandt became a hero for Tselkov after he discovered they were both born on July 15 – a fact celebrated in his 1971 Self-Portrait with Rembrandt on our Birthday, which is in the Ekaterina show along with another Tselkov self-portrait, with his wife Tonya.

The 1980s is the only decade in Tselkov’s career not represented in the exhibition. During this period he briefly explored Psychedelic Surrealism before producing a series of hazy monochromes, then advancing towards the luminous intensity that characterize the works he would paint in his sixties and seventies – and which form the chief focus of the Ekaterina show (three-quarters of the works date from after 1990). These are shot through with grating colour clashes (dark blue/turquoise, yellow/pink, lime-green/sea-green, crimson/purple) and feature Tselkov’s trademark male figure – gap-toothed, bald and bulky – in a variety of off-beat poses that invite comparison with the sculptures of Henry Moore. Patches of lighter paintwork ingeniously create a shimmering, luminous effect in dynamic compositions based on extravagant diagonals.

Alexandra Kharitonova’s hanging, based on colour rather than chronology or subject-matter, transforms the galleries into miniature cathedrals, with Tselkov’s paintings their stained-glass windows – reflecting Vladimir Semenikin’s conviction that Tselkov’s recent canvases represent the pinnacle of his career.

Kharitonova has a keen eye and sure touch, but it deserts her on one occasion. Tselkov’s sensational 1970 interpretation of The Last Supper, one of the most powerful group images of the 20th century, is relegated to the first-floor landing, sandwiched almost inconsequentially between two galleries, and comes into view immediately after the eye has been assailed by an even larger, sabre-wielding, scarlet, pink and orange apocalyptic Horseman halfway up the stairs, on loan from the Hermitage.

The Last Supper features a shimmering, port-red sea of twilit faces, clamouring for a drink like eager punters in some sleazy night-club; Jesus is portrayed at the bottom of the picture looking up, his eyes raised simultaneously to the ceiling and the viewer, his hands aloft in despair as if telling his Apostles (and humanity in general) to belt up and leave him alone.

It is tempting to see this disturbing image as an allegorical artist’s plea for solitude, not least because Tselkov shuns rather than seeks limelight.

Well, usually.

At the Moscow opening, where he and his buddy Yevtushenko were assailed by journalists, TV crews and a scrum of art-lovers, he looked as happy as a sandboy – roaring into his eighties with relish.