Публикации

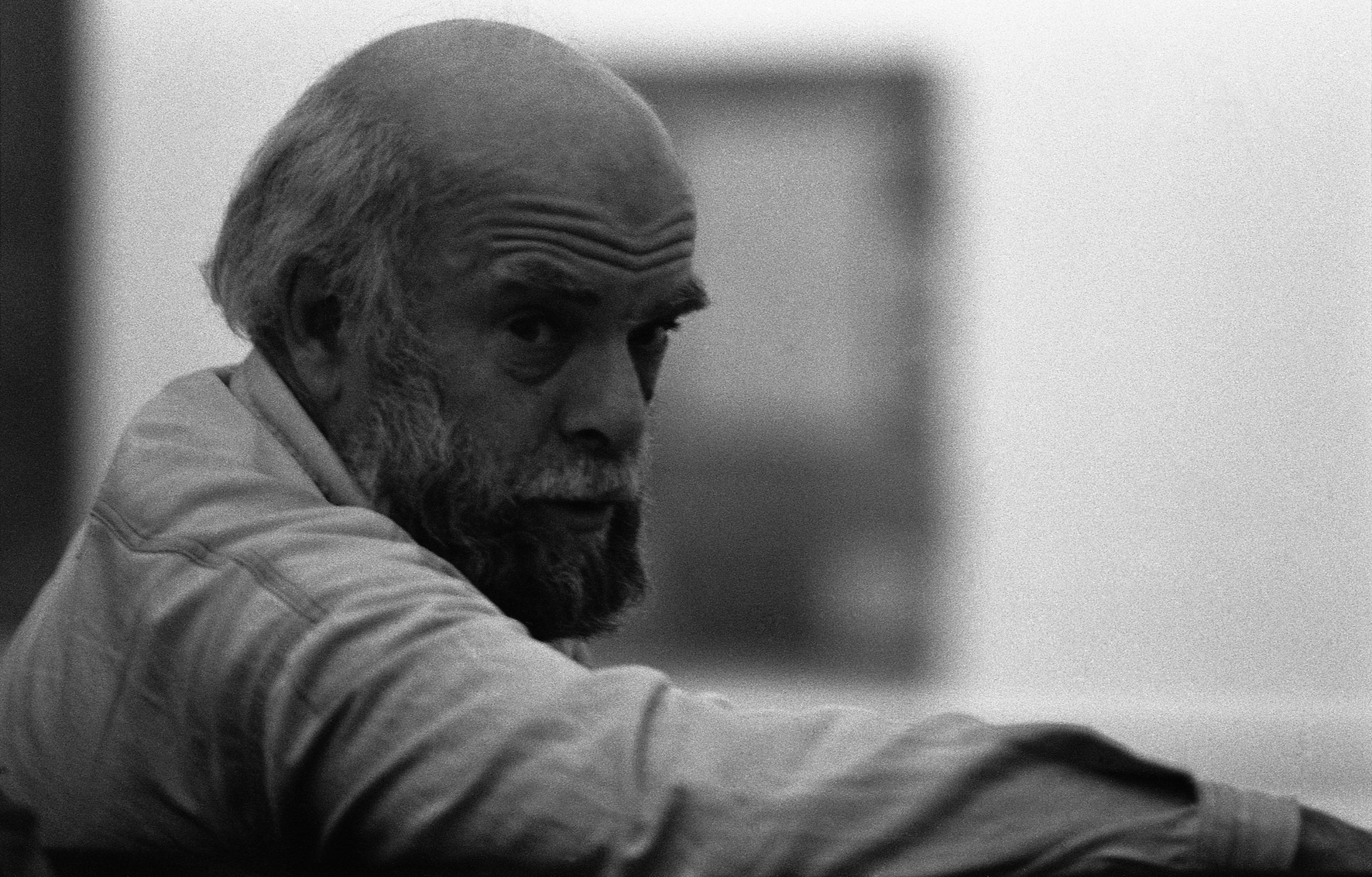

Mikhail Roginsky had little time for the label "founder of Soviet Pop" or, in fact, for any group at all By Franco Fanelli. Features, Issue 259, July-August 2014 Published online: 15 July 2014 Roginsky's The Red Door, 1965, is on show in Venice. It has also caused much misunderstanding of the artist’s work What strikes you most about Mikhail Roginsky (1931-2004) is that he did not give a damn about so-called “fine painting”. He declared this through his works but also his words. “For me the picture itself is nothing. The essential meaning of my works is always ‘beyond’ the picture itself. I have always been extremely interested in overcoming the typical artistic element in painting, of refuting it.” In other words, his concept of painting is not as “art”, if by this word one means “imitation”, “illusion”, “artifice”, but as an existential experience. It is no coincidence that Goya, who concentrated his spiritual legacy in the harshness of his Black Paintings, was one of Roginsky’s models. We also have to remember what was considered “art” in the Soviet Union during the Socialist Realist phase, when Roginsky was growing up. That is why his denial of painting as art and his own pictorial brutality should be seen in the light of his desire to be a painter, and a realist painter, without adhering to the official canon. For similar reasons, Georg Baselitz, who grew up in the German Democratic Republic, began to paint realistic figures, but upside down. The exhibition at Ca’ Foscari, one of the collateral events of the Venice Architecture Biennale, goes “beyond” painting, but also “Beyond The Red Door” (the title of the show), The Red Door being a piece from 1965 that has caused much misunderstanding of the artist’s work. It was the critic Alexander Glezer, the curator of the 1964 exhibition of dissident art in Moscow, who stuck the label “founder of Soviet Pop art” on Roginsky, who never accepted it. The Red Door is a real fire-protection door, albeit slightly shrunken in size (only 1.6m high). It is less like a ready-made by Marcel Duchamp to which some hapless workers at a past Venice Biennale gave a fresh coat of paint than certain interventions by Robert Rauschenberg or Jim Dine during their Neo-Dada phase. The Red Door was actually one of Roginsky’s many attempts to go beyond the illusionism of painting, to overcome the edges of the canvas and its flatness and perhaps also the limitations of a work as a vector of political messages. After emigration This exhibition of 120 works focuses on those dating from after Roginsky emigrated to Paris in 1978 and it reveals an artist who had nothing to do with either Neo-Dada’s emphasis on the work of art as an object, nor the artificiality of Pop Art. The rough surfaces and brushstrokes of Roginsky are completely unlike the hyper-realism of James Rosenquist, for example, and the intention with which the Russian artist painted everyday objects (rows of plastic bottles, then jugs and teapots floating in pictorial space) makes them light-years away from those painted by Jasper Johns or sculpted by Claes Oldenburg. If American painters interested him, it was the previous generation. He was attracted by the strained realism of Ben Shahn, for example, and the uneasy situations depicted by Edward Hopper. He saw works by both these artists in 1959 in an exhibition in Sokolniki Park, we are told by Richard Leydier, the author of one of the essays in the catalogue. Similarly, Roginsky’s series of “uninhabited garments” of 1991-92 have nothing in common with those by Dine except their subject matter. What distinguishes these and other works by Roginsky from supposed US models is a persistent melancholy that fits the Russian stereotype and can be seen today in the installations of Ilya and Emilia Kabakov. His interiors, which reveal Roginsky’s background as a set designer—the stoves painted with deliberate primitivism, without realistic volume or perspective, the clothes, still-lifes and the many human figures—belong to a painful existentialism combined with everyday intimacy that represent a kind of last refuge. This loneliness of the artist, the feeling of isolation and being under siege, have been written about by the curator Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev in her Documenta of 2012, citing Giorgio Morandi, among others. Roginsky was obstinately isolated and continued to be so in Paris, resisting any contagion by the Nouveau Réalisme even though he began inserting fragments of three-dimensional collage into his pictures in the 1980s. He passed through the years in which Conceptualism banished painting, and then the years when it came back into fashion with Neo-Expressionism and the Transavanguardia. But just as he did not give up on paintbrush and canvas in the 1970s, he did not climb on the Postmodern bandwagon in the 1980s. However tempting it is to consider him part of the “Bad Painting” movement that flared up again in Britain in the 1990s (remember Martin Maloney?), it is certain that Roginsky’s painting does not share its iconoclastic cynicism. Even the writings, slogans, statements and insults (“everything is shit except for urine”) that invade his paintings from the middle of the 1980s are like deranged lines of poetry, wild words that turn the paint surface into a manifesto, inscription, anarchist graffito or epitaph. And unlike the Transavanguardia, there is no trace in his work of nostalgic references. Unlike Bad Painting, it is also very clear that Roginsky really identifies with his figures, who are often waiting for a bus or metro (as in the works from after 1993, when Roginsky was able to return to Moscow). There are waiting figures, figures on the threshold, as in two works of 1989. The threshold (and so the door, whether red or otherwise) perhaps becomes the metaphor for an artist in no man’s land. Roginsky was no Outsider artist (he was a professional with a solid training), but neither was he an orthodox participant in the rites and strategies of contemporary art and its market. He was an artist who painted, he said “to defend certain values and fight our plasticised culture with them”. As such, he was a dissident not only from political regimes, but also every form of hypocrisy passed off as art. “Beyond the Red Door”, Ca’ Foscari, Venice, until 28 September. Curators: Ekaterina Kondranina, Elena Rudenko and Eugene Asse, with the support of the Roginsky Foundation